Archive

Muscle Memories

(Last week, I had already decided I would post post this story today. Coincidentally, today also marks the death of Les Paul, inventor of the electric guitar and maker of the Gibson Les Paul guitar. I guess some things just happen that way. This story is based on a true events. Enjoy. 😉

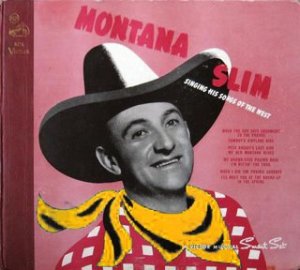

- Montana Slim

When I was growing up, some of the homes in my neighborhood were small, simple one-room cabins on wooden skids. They were originally built to be towed behind a double-tracked Bombardier snow vehicle during the long winter commercial fishing season on Great Slave Lake. But many eventually ended up as permanent homes. Not far from our house, one such cabin became the home of my Uncle Frank. A fisherman himself between long bouts of drinking, Frank worked for my father to support his lifestyle, a lifestyle that could only be described as a conundrum because somehow it worked in practice, but not in theory. Like most of his drinking buddies, he should have been dead long ago. But he was a master at adaptation, and in terms of survival, he was among the fittest.

Frank knew he was an alcoholic, but he didn’t see it that way. Once while staggering in downtown Hay River, he was stopped by a local policeman and asked if he had been drinking that night. With a friendly wrinkle of his nose, he replied in a whispered voice, “Nope. Not tonight, Officer. But I have been known to imbibe on occasion.”

Then he paused when he realized the young cop might be carrying money. It was almost as though Frank could smell it on the people he met. Immediately, something came over him. From far down inside came a personality that managed his life, the one who made sure he had enough to drink, smoke and eat for another day. His body stopped swaying, his stance relaxed and his eyes twinkled.

It was such a subtle and automatic shift that even Frank probably didn’t notice it happening at all. He had done this hundreds, perhaps thousands of times before, so his body could run on muscle memory alone. Frank the Drunk could just sit back and watch as Frank the Manager took over.

He lowered his head and asked quietly, “Hey, you think I can borrow a couple bucks for some tobacco, there, Constable?” As always, Frank the Manager actually believed he would put the money toward tobacco or food. Frank the Drunk, however, knew better.

Uncle Frank was a quiet, soft spoken man, who slipped through the neighborhood like wood smoke. He took no sides in family disputes, always had time for the neighborhood kids and made lifelong friends with those who shared his love for the bottle. He did this because these people were his support network, his means for survival.

And while his voice and manner were restrained, his big hands spoke volumes. His fingers were scarred from decades of pulling fish nets from the icy waters of Great Slave Lake, calloused from sawing, chopping and hauling firewood at forty below, and hardened by twisting countless screw caps and pulling bottle corks.

But deep within the cracks of those thick hands also lay the secrets of a brilliant five-finger guitar picker. With his right hand, he could pluck base with the thumb, strum rhythm with the three middle fingers and play lead with the pinky – all at the same time. His left hand played a loose choke style that allowed him vast space to move easily, to shift, to stretch, to improvise. With four fingers slung around the bottom of the neck, the thumb hung over the top like a hook, ready to carry the bass line. There was far more freedom to move about on that slim guitar neck than all the floor space in his little shack.

On those days when I could hear his beat up Fender Stratocaster electric guitar belting out Chet Atkins’ Wheels or Les Paul’s Blue Skies through a tiny one-speaker amplifier, I would drop in for a visit. Sometimes I would find my cousins already there sitting in front of this thin, chinless, greying man, guitar in hand, shakily gurgling back cheap 5-Star rye or rolling his own cigarettes. Sometimes, when the shakes got too bad, he would get one of us to roll his cigarettes.

In one corner of his tiny home sat a small airtight wood stove. In another, an old wooden table. In a third corner was a narrow steel-framed spring bed with a heavily-stained mattress and an eider down blanket. Behind the door, a stack of Wrestling magazines from the mid-60s, the top issue of which featured wrestler Haystacks Calhoun. He was warning fans not to come into the ring again after one fan did in an effort to stop his bleeding from a razor blade cut.

Up high near the ceiling on the back wall, hung a small portrait of Jesus Christ, his hands held over his chest in the shape of a heart, a bright white light emanating from within. And as if projected from that light, on the opposite wall was a photo of a young Wilf Carter in his white cowboy hat and powder blue suit, leaning on his guitar. The singer/songwriter had a wide grin on his bright white face.

Most times Frank’s hands shook so violently when he was sober that he rarely played a tune until he had first put away a few hard swigs. Within minutes, however, he would pick up the guitar and you could see his whole body begin to mellow, the range of control extending throughout his wrists and hands as he flexed and rolled each finger through a series of exercises. He was waking up.

Then he would warm up by finding his place on the Strat, a guitar he had won in a poker game with a fisherman on the lake. He would pluck a few random chords just to get the feel of the strings, the steel frets and the pearl inlaid maple fret-board.

If you have ever had the pleasure of playing a Fender Stratocaster you will understand the ease with which it allows players to maneuver about the instrument. The slim neck, the low set strings and the sharp, clean twang attracted pickers from all music genres – from Blues to Jazz, from Rock to Country, and from Reggae to Metal. And from all walks of life – from cowboys to Indians, and from hobos to fishermen.

When sober, my Uncle Frank was a man of very few words. But as his fingers loosened, so did his tongue. And the stories that followed were always about musicians or politicians or movie stars or wrestlers – all stories from magazines he’d found somewhere or heard on CBC radio. One time he told us the story about one of his favorite musicians.

“Montana Slim – now there was a great singer/songwriter”, he would say after shooting back consecutive gulps of Five Star rye whiskey right from the bottle. He winced as it burned his throat, his bottom lip extending out, wet, quivering. He continued, “The Father of Canadian Country Music. Heart of gold in every song. A guy who understood kids, hobos and cowboys like nobody else. I guess he was all three at some time in his life. And man, could he yodel! The called him the Yodeling Fool.”

I find that most guitar players can either talk or play but have trouble doing both simultaneously. One task or the other usually suffers from a lack of focus. Uncle Frank didn’t have that problem. While he spoke, the muscles in his fingers moved about locked in some deep sense of their own memory. Frank the Storyteller and Frank the Guitar Player operated independently of each other.

“I don’t know why,” Frank would continue, “but the best damn Country and Western singers and songwriters come from back East. Look at the great Hank Snow, and now this new guy, Stompin’ Tom Conners from Skinners Pond. All masters.”

With that, he began to pick the melody of Bluebird on your Windowsill way up high up on the neck in the harmonics section, gently touching and rubbing each string with such dexterity that beneath those calluses, each note rang out like a tiny hand bell.

“Montana Slim liked to visit the kids in the hospital on Sundays in Calgary and play for them,” he said. “What a guy. Heart as big as the prairie sky.”

By now everyone had heard the story of how Montana Slim’s real name was Wilf Carter and how a woman at his recording label just picked the name out of thin air and put it on his records and how he became a star in the United States under that name and how we only ever knew him up here as Wilf Carter. But to Uncle Frank, he was always Montana Slim.

And so the guitar picking, the drinking and stories of Montana Slim, at fourteen, hitching a ride on a freight train heading west, just like so many other hobos, would go long into the cold, winter dark.

* * *

Having been young at the time and raised nowhere near farmland, it was difficult for my cousins and I to relate to the music of our parents. Our first choice was Rock. So, in the early seventies, it came as a bit of a surprise when we discovered that our small northern fishing town on the south shores of Great Slave Lake of perhaps two thousand would be hosting the first ever, real cowboy rodeo north of the sixtieth parallel. Everyone on my block was excited. This was the Northwest Territories and most of us had not so much as ever seen a cow, let alone ridden a horse.

But if you happened to be in the neighborhood on that day of the announcement, you may have heard a muffled “Eee-hah!” coming from Uncle Frank’s cabin when they also announced the headline act – none other than the Father of Canadian Country Music himself, Wilf Carter.

* * *

After a long dry summer, the rodeo weekend arrived in mid-August. Pickup trucks and cattle and horse trailers filled parking lots. They plugged driveways and campgrounds and spilled into the streets of Hay River. Northerners, some wearing cowboy hats and boots for the first time, greeted each other with funny things like, “Howdie”, or “Good Day, Ma’am”, or “Nice day, ain’t it?”. For weeks, the stench of cow and horse shit drying in the late summer sun would hang over this small town. For the uninitiated, even for those of us weaned on the smell of rotting fish, this was simply unbearable.

But we tried to pay little notice, because today was Friday, and tonight, Wilf Carter would be the opening act for the rodeo with an 8 o’clock concert in the arena. My cousins and I, realizing we didn’t have enough money for concert tickets, wandered around downtown eagerly watching the activities and hoping to catch a glimpse of the Father of Canadian Country Music.

The rodeo itself was to begin Saturday morning in the hockey arena where the ice surface had been swapped for a thick layer of brown dirt. Metal gates and fences were installed inside and out to help manage the animals. The concert stage was set at center ice, facing the bleachers. Young men in cowboy hats and jeans moved equipment, checked sound levels and set up lights. Electrical cords ran everywhere like spaghetti. But there was no sign of the Father anywhere.

After dinner that night, we bicycled the three miles back to the arena. When we arrived, the lobby was roped off and the entrance was full to capacity. It was rumoured that Mr. Carter would pass through the lobby en route to the stage so we might get to see him after all. As we strained our necks to look above the crowd, I spotted Uncle Frank. I squeezed through to the front of the mass and found a place along the rope a few feet from him. He was emaciated and shifted uneasily, nervous at being in such a large crowd. His trembling hands tightly clutched a pen and his picture of Wilf Carter. He looked like he’d had neither food nor drink in days.

Suddenly, the crowd began to hum with anticipation and before I knew it, there He was strutting through the lobby. Looking much, much older, thinner and shorter than in the picture I had seen for so many years, Wilf Carter smiled and waved to the people around me who began to cheer and call his name. I could see my Uncle trying to call out but his feeble voice could not be heard above the din. Frustrated, he shook his head and held up the photograph.

Then it happened. Wilf Carter saw the photo Frank was holding and turned and came over and stood in front of him, smiling and shaking my uncle’s hand. Through the noise of the crowd, I could just barely make out the conversation. Frank stammered something and Wilf Carter leaned in closer to hear him.

Frank said, “Mr. Slim, uh Montana, I have listened to your music for as long as I can remember. I think you are the best damn singer/songwriter in this country and I was wondering…?” Then he stopped and looked down at the old photo in his hands. The smiling Mr. Carter leaned in a bit closer to hear my uncle’s faint voice. The crowd grew louder.

“Could you…?, Frank’s voice cracked.

Wilf Carter leaned in even closer. So close, Frank could now smell him. That’s when I saw Frank’s eyes shift from the photograph to his trembling hands and a sudden transformation took place. With a smile and a twinkle in his eye, Uncle Frank the Manager looked up, wrinkled his nose and quietly asked, “Montana, ya think I can borrow a few bucks to get some tobacco and a hot meal?”

A cold pallor descended on Wilf Carter. He slowly pulled back and straightened up. The smile was gone.

And that’s when Montana Slim, the Father of Canadian Country Music, the Yodeling Fool, this Champion of Hardworking Cowboys, Sick Children and Wayward Hobos became Wilf Carter the Old Man.

He pursed his lips and to this thin leaf of a Cree man, trembling in the wind before him, he said, – as he had probably said a thousand times before – “Fuck right off, you goddamn bum!”

Then he turned and walked away, much to the dismay of the cheering crowd.

Frank stood there, his bottom lip quivering, his lifeless eyes on the prize in his hands, his back broken. Then he, too, turned and, like smoke, faded into the fray.

* * *

Wilf Carter’s image no longer hung projected from the chest of Jesus Christ the next time I went to see Frank. He never spoke of Montana Slim again. He still played his guitar and told stories, but was careful not to speak too highly of anyone thereafter.

Finally, in 1988, a full eight years before Montana Slim, Uncle Frank died. On that cold winter night his heart gave way while he slept, and with the last tendrils of smoke from his chimney, Uncle Frank slipped quietly through the neighborhood past the homes of friends and family for the last time.

He left not knowing that I had overheard the conversation in the arena lobby that day. He slipped away probably believing that he had made no difference in this world, that he had left neither pain nor hope behind.

He was wrong, of course, because in the years that followed when my brothers, nieces, nephews, cousins and I would pick up our guitars to play for our kids or in bands or in concerts or recording studios or just play for the sheer joy of playing, we would be reminded every day what a true gift he had.

And even today, when I listen to five-finger masters like Randy Bachman, Mark Knopfler, or Lindsay Buckingham, I can still hear my Uncle Frank’s fingers, hardened and cut from a lifetime of fishing and drinking, scraping across those steel-wound strings with each chord change and I take comfort in the thought that a good story is not very far away.

*

Frederick A. Lepine

Originally written at

The Banff Centre for the Arts

North Residency

January/February 2007

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

Blog Stats

- 6,777 hits